- Home

- News

- General News

- How a protective...

How a protective coating can improve lithium batteries

28-01-2026

Scientists have demonstrated how a protective polymer coating can overcome obstacles that make high-energy-density batteries not available commercially yet. Their results are out now in the journal Carbon Energy.

Share

Lithium metal anodes are promising materials for high-energy-density batteries. However, their applications are not yet a reality due to long-term safety and performance issues, which are caused by the high lithium anode reactivity, which leads to dendrite formation, interfacial degradation and mechanical stress during charging cycles.

When a liquid electrolyte is used, uneven deposition of lithium ions at the anode surface during the charge phase caused formation of needle-like dendrites that can pierce the separator, causing short-circuits and safety risks and lead to explosion. Moreover, the solid electrolyte interface formed in the first charge/discharge cycles breaks down easily due to lithium’s high reactivity, leading to parasitic reactions and poor cycling stability. In solid-state systems, rigid electrolytes amplify electro-chemo-mechanical strain, further damaging the interface and accelerating failure. Altogether, these coupled chemical and mechanical instabilities limit the long-term safety and performance of lithium metal batteries.

Stopping uncontrolled growth

To tackle these challenges, a team led by the University of Groningen has studied protective coatings deposited on lithium metal to regulate lithium-ion flow and prevent dendrite nucleation. In particular, they developed and studied at the ESRF a soft functional coating based on thiourea H‐bonded supramolecular polymer.

“These solid polymer electrolytes are very interesting, but exhibit too low ionic conductivity compared to liquids to be used as electrolyte. However, they have peculiar mechanical and adhesion properties that triggered us to use them as a coat to solve the uncontrolled growth”, explains Giuseppe Portale, professor at the University of Groningen (The Netherlands) and corresponding author of the study.

|

|

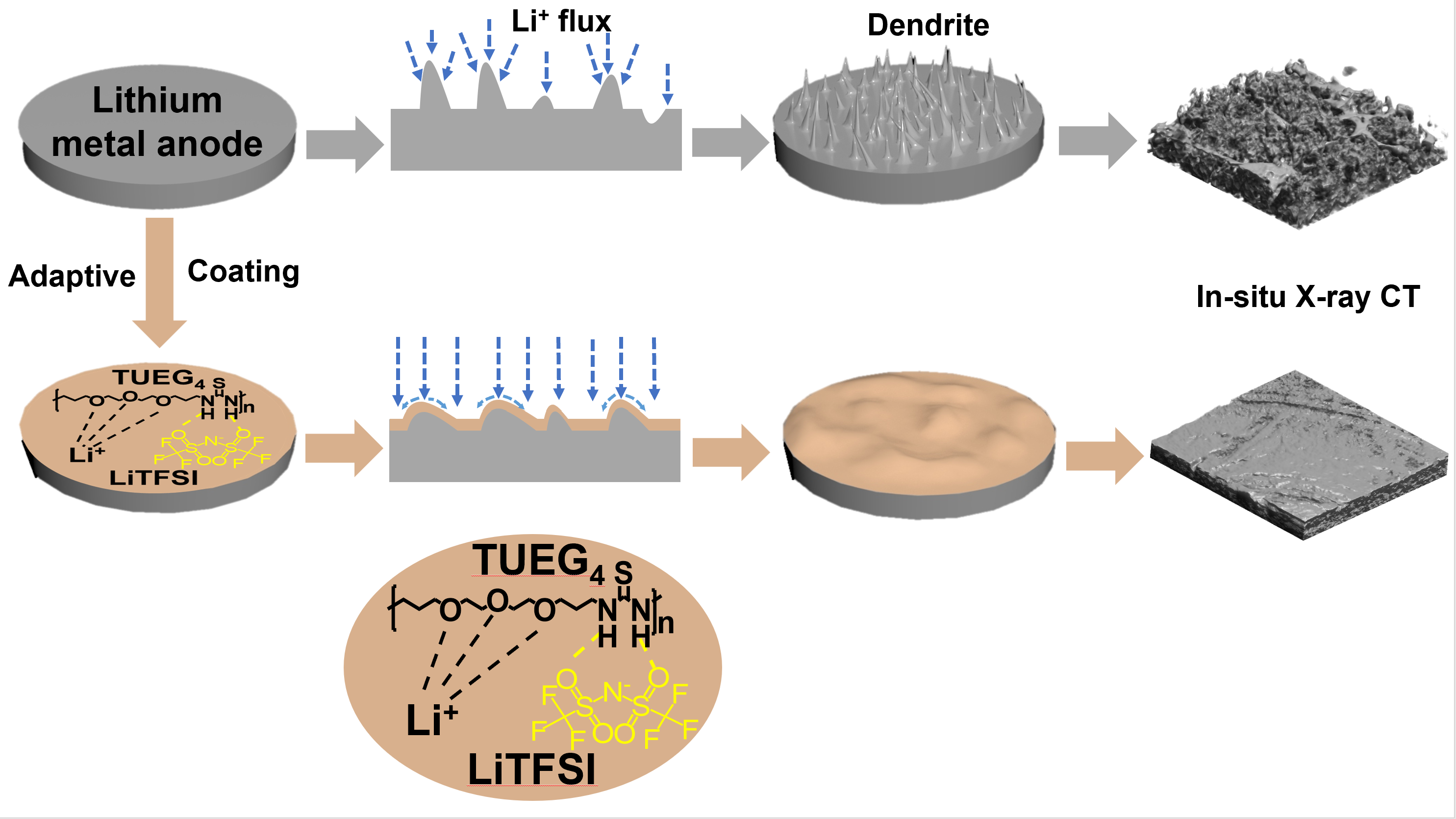

Schematic illustration of the Li deposition behaviour without and with the adaptive protective layer. Credits: Zhang, Y. et al, Carbon Energy, 2025 |

Advantages include the fact that the polymer is very easy to coat, very stable (battery can be cycled 500-100 times without issues) and shows self-healing properties, which effectively extends the life of the battery.

The coating mechanism

Scientists still do not understand the mechanisms of these polymer coatings. That is what led the team to beamline ID15A, at the ESRF, where they carried out phase contrast X-ray tomography on the model batteries.

“Following excellent electrochemical performances, we needed to verify if our polymer coating really suppresses the uncontrolled reactions at the lithium metal interface, but we had the issue that these batteries are encased in stainless steel. So, we used the high energy beam available at ID15A to look in-situ inside the battery. However, the contrast between the lithium metal, the polymer and the electrolyte is very low, so we had to engineer a way to go through the stainless steel but at the same time have enough sensitivity to detect what goes on inside the battery. The results were amazing, explains Portale. We could clearly demonstrate that the use of our thin polymer coating completely suppresses the formation of unwanted lithium structures during cycling.”

The team combined these analyses with X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and COMSOL simulations. They discovered that the polymer they used does degrade the conductivity in the system, but instead it shows reduced resistance over cycles and dramatically improves the battery lifetime by enabling a homogeneous deposition of lithium ions as a result of an adaptable mechanical/ionic conductivity behaviour during charge-discharge cycling. The researchers still detected some grains at the anode interface, but much more contained than in the absence of the polymer coating, as they do not grow in an uncontrollable way.

The next step for the team is to study these coated batteries in operando, while they are functioning. The ESRF will host a University of Groningen’s PhD student who will deepen into this subject.

Reference:

Zhang, Y. et al, Carbon Energy, 2025; e70082 https://doi.org/10.1002/cey2.70082

Text by Montserrat Capellas Espuny

Top image: In-situ X-ray computed tomography (XCT) three-dimensional reconstructions of the lithium metal surfaces of (below) bare Li and (above) Li@APL electrodes.